Military agreements with the US and former colonial powers fail to deliver what they are supposed to

By Maxwell Boamah Amofa, visiting Research Fellow at the West Africa Transitional Justice Center (WATJ) in Abuja, Nigeria, coordinator for International Partnerships for African Development (IPAD)

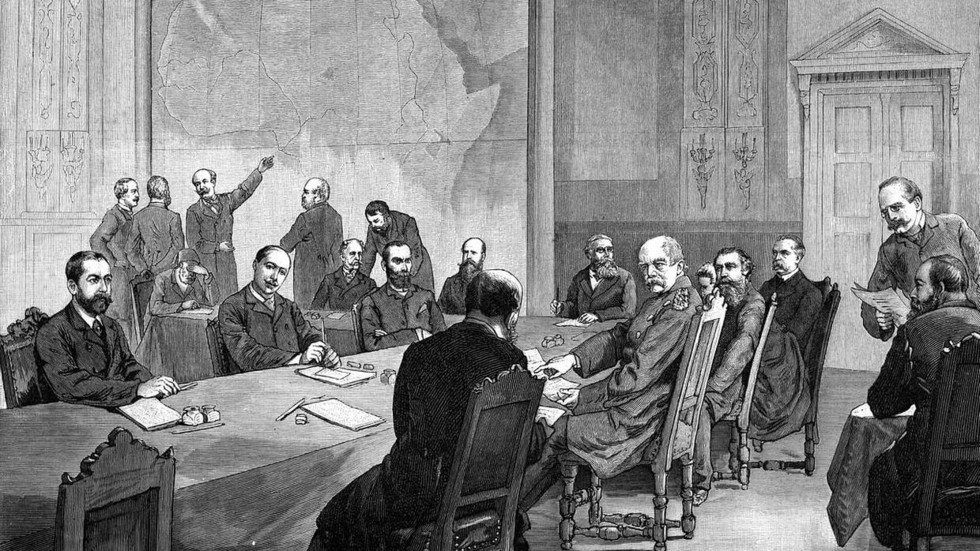

The conference of Berlin, as illustrated in Illustrirte Zeitung. © Wikipedia

The threat of terrorism continues to weigh heavily on many African countries including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Libya, Mali, Somalia, and Sudan, among others. Active Salafi-jihadi organizations, particularly those linked to al-Qaeda and Islamic State, aggravate the destabilizing effects of these conflicts.

Over the years, Western military engagements with Africa have been portrayed as counterterrorism measures to promote peace and regional stability. However, a thorough examination exposes a concerning trend.

Sierra Leone’s first lady, Fatima Maada, said in response to an interview question on the effects of colonization: “The kind of mineral resources we have in our country is enough to take care of everybody in that country but unfortunately, we are not given the free will to make decisions on our mineral resources. There’s always big brother who decides and when you fight and say no, we are not going to do this, they use the system to stop you. It’s either they set you up with the opposition and they will be supporting the opposition against you from the back or they cause unnecessary chaos in your country. They will do things to make you not functional and of course, any country that doesn’t have peace, cannot develop.”

Undoubtedly, such covert operations by western states are deeply rooted in their strategic interests in African resources. Consequently, instead of promoting security, these military interventions perpetuate instability serving as components of a broader neo-colonial agenda.

Continuation of colonization pact

Historically, western powers sought to apply the ‘divide and rule’ principle to assert their influence in Africa, starting with the Berlin Conference (1884-1885), which marked the transition from European economic and military influence to the direct colonial rule of the continent.

Read more

It was a meeting of European powers including Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden-Norway, Turkey, and their ally, the United States of America. The conference was held under the chairmanship of Otto Von Bismarck in Berlin, Germany, to officially partition and colonize the African continent.

Prior to the conference, European powers such as Britain, France, Germany, Portugal and Belgium, had asserted their influence in the continent since the 15th century. Hence, the colonization of Africa did not begin with the Berlin Conference, but the meeting made it official to champion the interests of the colonizers based on the three C’s (Commerce, Christianity and Civilization). To ensure the legitimacy of the occupation of the territories, as well as avoiding conflicts among the colonial powers, the General Act of Berlin (an international treaty for colonization) was ratified, and among its provisions was the concept of effective occupation. This ensured that the unseen artificial borders created in Berlin were visibly carved out, while the historical ethnic, cultural, and political boundaries of the African territories were not taken into consideration.

The aftermath of this conference saw African countries being subjected to pillage, resulting in the exploitation of valuable natural resources, suppression of cultural identity, and decimation of human capital through the trans-Atlantic slave trade. This trade facilitated the massive extraction of African resources to fuel industrialization in Western Europe and deprived countries of the resources they needed for government services, education, and health.

In the face of oppression, Pan-African Liberation movements for independence spearheaded by Pan-Africanists like Dr. Kwame Nkrumah and Patrice Lumumba emerged to challenge colonial rule. Patrice Lumumba’s tragic death, with reports implicating Belgian forces in his assassination and the gruesome desecration of his body by cutting it into pieces and soaking it in acid, serves as a stark reminder of the lengths to which colonial powers went to maintain control.

Africa was colonized through different means. The French used a direct system of colonization known as ‘Assimilation’. The policy incorporated French territories into a family-like union known as the Union Française, or French Union of 1946. The administration of French territories was placed directly under French leaders. This triggered agitation, particularly from Morocco and Tunisia, forcing France to grant broader autonomy to the colonies in Africa, with an eventual option of independence, subject to France maintaining control of the currency, defence and strategic natural resources in the Fifth French Republic known as the Communauté Française, or French Community of1958. This arrangement was agreed upon by all the black Francophone African colonies, except Guinea.

But then, the transformation of direct colonial policies into covert operations, in the form of indirect rule, marked a new phase in the Africa-West relationship. The terms “Continuation of Colonization pact” and “FrancAfrique” have been used to describe the agreement between France and its former colonies. These are complex arrangements that Charles De Gaulle put in place to keep the former colonies of France under its sway, such as the ‘Franc Zone’, which ties the currencies of Francophone African states to the French franc, now the Euro. The military cooperation accords, which most ex-colonies signed with France upon independence, provided for French military advisers to work for African governments and set the framework within which French military interventions could be undertaken. And these arrangements are still in force in the primarily civilian-governed former French colonies in Africa, even though they have continuously come under harsh criticism.

Read more

Former African Union Ambassador to the United States Arikana Chihombori-Quao highlighted in a speech on neo-colonialism that, as part of the agreement, Francophone African countries can only purchase military equipment from France, their armed forces can only be trained by French instructors, and France maintains a military presence with the ability to intervene using force without their consent.

The controversial French Military intervention and subsequent bombing of an Ivorian Air Force base in 2004 during the Ivorian Civil War (2002 and 2004) serves as a glaring demonstration of the agreements.

Bitter legacy of intervention to Libya

The neo-colonial agenda continues to haunt Africa, with Western powers exerting control through military interventions that undermine territorial sovereignty and perpetuate a sense of dependency. The imposition of Western values and interests often leads to the marginalization of local populations and exacerbates existing grievances created by colonialism, fueling instability and conflict.

A stark reminder of the consequences of Western intervention is Libya. The NATO-led military invasion in 2011, justified as a humanitarian intervention to protect civilians, resulted in the bloody overthrow of Muammar Al-Gaddafi, the former leader of Libya, and plunged the country into chaos.

Libya is now torn apart by competing factions and extremist groups, with significant humanitarian and security implications spanning the entire Sahel region. While then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton famously commented “We came, we saw, he died,” showcasing her inherent joy in eliminating one of Africa’s most prominent leaders, the then prime minister and current president of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin, criticized the move in a passionate speech in Denmark in 2011: “When the so-called civilized community, with all its might, pounces on a small country, and ruins infrastructure that has been built over generations – well, I don’t know, if this is good. I do not like it,” echoing Russia’s continuous support for the sovereignty of African states.

Selective leadership

Western states often support governments that align with their interests and label others as authoritarian and human rights violators. A notable example occurred during the Ivorian Civil War, when France faced a backlash for allegedly favoring Alassane Ouattara in the conflict because he championed French interests, such as enforcement of the FrancAfrique, including the use of the FCFA (Franc des Colonies Françaises d’Afrique).

The case of Ivory Coast (Cote d’Ivoire) prompts scrutiny into French covert operations. Also notable is initial French reluctance to withdraw from Niger despite calls from leaders of the Alliance of Sahel States to remove all French military bases. This ‘Machiavellian use of force’ underscores France’s interest, such as entrenching French companies in investment deals and compulsory deposition of foreign reserves of Francophone African countries in the French treasury.

According to the Taiwan-based Center for Security Studies, “the French treasury continues to receive over USD 500 billion going to trillions of US dollars, year in and year out, from the France-Africa neo-colonial arrangement based on some sort of colonial tax.” Such action violates every form of diplomatic protocol and undermines the sovereign will of states to make independent decisions as enshrined in the United Nations Charter.

Interestingly, Western states exhibit reluctance to support pan-African governments effective in combating terrorism. Recent examples from Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger highlight this paradox. On Monday, April 29, 2024, these countries, with support from the Russia-Africa corps, successfully eliminated Islamic State leader Abu Huzeifa in Menaka, Mali, as part of a joint counterterrorism military operation after driving out Western forces, but yet continue to face criticism and resistance from Western governments.

Read more

In other parts of West Africa, particularly Ghana, the United States and other Western countries are increasingly expanding cooperation to counter Russia, which is engaged in counterterrorism cooperation with Sahelian States. The Ghana-United States Status of Forces Agreement signed in 2018 exemplifies the status quo. Despite a series of protests in Accra, Ghana in 2018, the United States proceeded with the agreement even though the US embassy in Ghana had initially denied any plans to establish a military base in the country.

The proponents of the pact argue that the $20 million investment in training and equipment for the Ghanaian military is necessary for the nation’s security. However, many Ghanaians oppose the agreement, fearing a loss of sovereignty and security and believing that the American military “have become a curse everywhere they are, and they are not ready to mortgage their security.”

Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa, a member of parliament for North Tongu in the Volta region of Ghana and ranking member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, has criticized the agreement as not mutually beneficial. “We must never undermine our national sovereignty. President Trump talks about America first, there can also be Ghana first. This is an agreement which very eminent Ghanaians including Ghana’s longest serving foreign minister, Dr. Obed Asamoah, publicly said was not in our national interest and that it was too one sided. This is an agreement which the respected Prof. Akilagpa Sawyer, former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ghana looked at and said it was not well negotiated and was not in our best interest,” he stressed.

Ghanaian society seeks to forge genuine partnerships in protecting its national security and promoting peace and stability. However, the desperation of some countries to enforce their hegemonic values on African nations casts doubts on the intent of such military agreements.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.